* * *

I want to start out by commenting on a quote that really stood out to me from the article "Using Twitter for Civic Education in K-12 Classrooms" (Chapman and Marich, 2020). In the paper, one high-school English teacher is interviewed about his teaching practices that use Twitter as a key element of class discussion. This is his opinion of 'digital citizenship':

I really appreciate him calling attention to this perspective, because it's something I totally agree with. Almost every career path nowadays (in the US) requires some level of digital literacy. This is true as well for civic participation and politics in general. Just think about how many forms and processes have been moved online, and how much campaigning is done through social media and personal websites. Someone who is not fluent in digital culture and skills is certainly being excluded from their right to participate fully in public dialogue and action. If we fail to establish a solid educational baseline for our students' digital literacy, they will inevitably be more excluded from public life and will lead less empowered, less critical lives.

This week in my classroom, I overheard a very memorable conversation. Two students who sit near my desk were chatting after having finished their assignment. J leaned over to ask N whether he would sign up to go fight for Israel in the war, if American citizens were called up. N was confused. Why would an American need to go fight in Israel? J was even more confused. N, don't you know there's a whole war going on between Israel and Palestine???

Clearly even two people who are in the same age and friend groups can have wildly difference experiences in and exposures to digital spaces. Even more clearly, this ignorance of information spread primarily through digital means could have a real impact on someone like N, who wouldn't have seen a draft coming at all.

Their conversation went on. J named the war, and N expressed some vague understanding. Then J got back to her original question: she had seen a poll on instagram asking whether people would go to fight for Israel or not, and so what would N have picked? He didn't know. He was ambivalent. How could he engage this critical conversation after only a few seconds of knowing a war was even on? And furthermore, how could J conceptualize that there might be more alternatives to the situation than just this binary poll choice? Whoever had posted this seemed to hold Zionist beliefs, but it was unclear if J was aware of this either. Her social media exposure is worlds different from mine, despite only having 5 years difference in age. The digital spaces I frequent are strongly pro-Palestinian, and generally feature more objective and thorough interviews and professional perspectives.

J is generally one of our more engaged and well-practiced students in literacy, so I was somewhat disturbed to overhear this conversation. She has brought up some fascinating and critical perspectives on texts we read in class, but seemed to engage with digital texts as something flippant and at face-value, even when the content of those digital texts and posts are objectively more urgent and "real".

Having experienced this interaction just this past week, Chapman and Marich's article felt all the more relevant. I feel a responsibility to prepare my kids for the world they will have to live in, and what we teach right now is not doing that job. These students will graduate and perhaps never pick up a novel again. Never pick up any long-form news reporting or piece of informational writing. The fantasy is that our classrooms will magically motivate every child to suddenly love reading for the rest of their lives, but that isn't practically possible. I know I won't reach every kid that way, and I also know that teaching about those "real" digital spaces and skills has a higher likelihood of catching those students who will not be motivated by traditional literature.

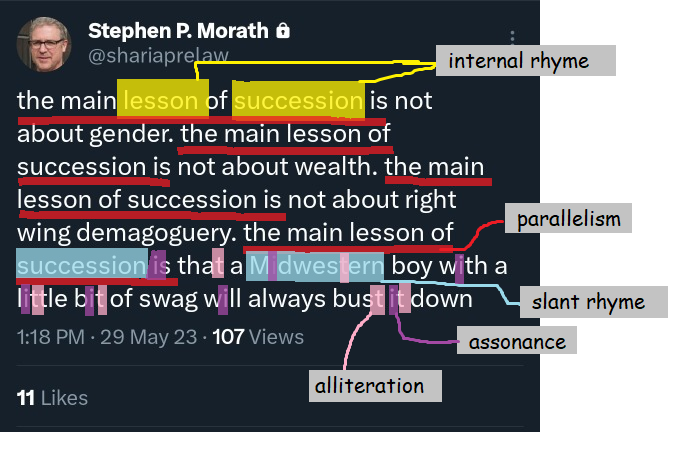

I have got to thinking on my own lately about noticing traditional "literary" elements in new digital texts. For example, I saw a screenshot of a tweet about the HBO series "Succession", and made this diagram to post on my own social media (along with a mini-essay analyzing all my notations and the overall message of the tweet):

It was a lot of fun playing with this concise text in more formalized, analytical ways! And the act of writing up my thoughts served as a tool to organize my thoughts and personal conclusions in the first place. I would be overjoyed to help bring this joy to my own students. I felt like this interaction helped me bring out a better understanding and enjoyment of this show I already was invested in. Plus, it just felt satisfying to exercise my brain in ways that didn't feel like some contrived analysis assignment. Once again: it felt "real".

So far, my general philosophy for using digital tools in the classroom is that the use of these tools should be to give students more agency in our shared space. What have they seen online that they want to talk about? What tools do they already use that we can incorporate (and skip the unweildy 'tutorial day' lesson)? How can we use digital technology to help every student share their voice with peers and the wilder world? These are the benefits of digital tech that are far less possible with analog technology. If something is possible with analogue tools, I would much rather enagage the students' physical bodies and voices as much as possible. But the advantages of digital tech have their place too, and I'm looking forward to finding where it will best fit in within my teaching career.

* * *